By Clifford Akumu

Across the open plains of Lching’ei Village in Samburu County, a herd of goats roam the scape, nibbling at tiny twigs of stout acacia shrubs scattered across the expanse.

Further afield, manyattas – dome-shaped temporary pastoralists shelters made of mud and sticks – dot the village like overgrown ant-hills.

Not far away, Hellen Nasha Lelegwe’s one-acre farm rolls by with rows of leafy sukuma-wiki and amaranth intercropped among maize, with napier grass seated on the edges of the farm.

The veggies, says Mrs Lelegwe, have been an important source of food and nutrition for her family and fellow villagers, particularly during the searing drought that tore the region’s food security apart.

She grows a variety of vegetables, ranging from sukuma-wiki, cabbages, onions, tomatoes, saget, African nightshade (managu), green pepper to sweet potatoes.

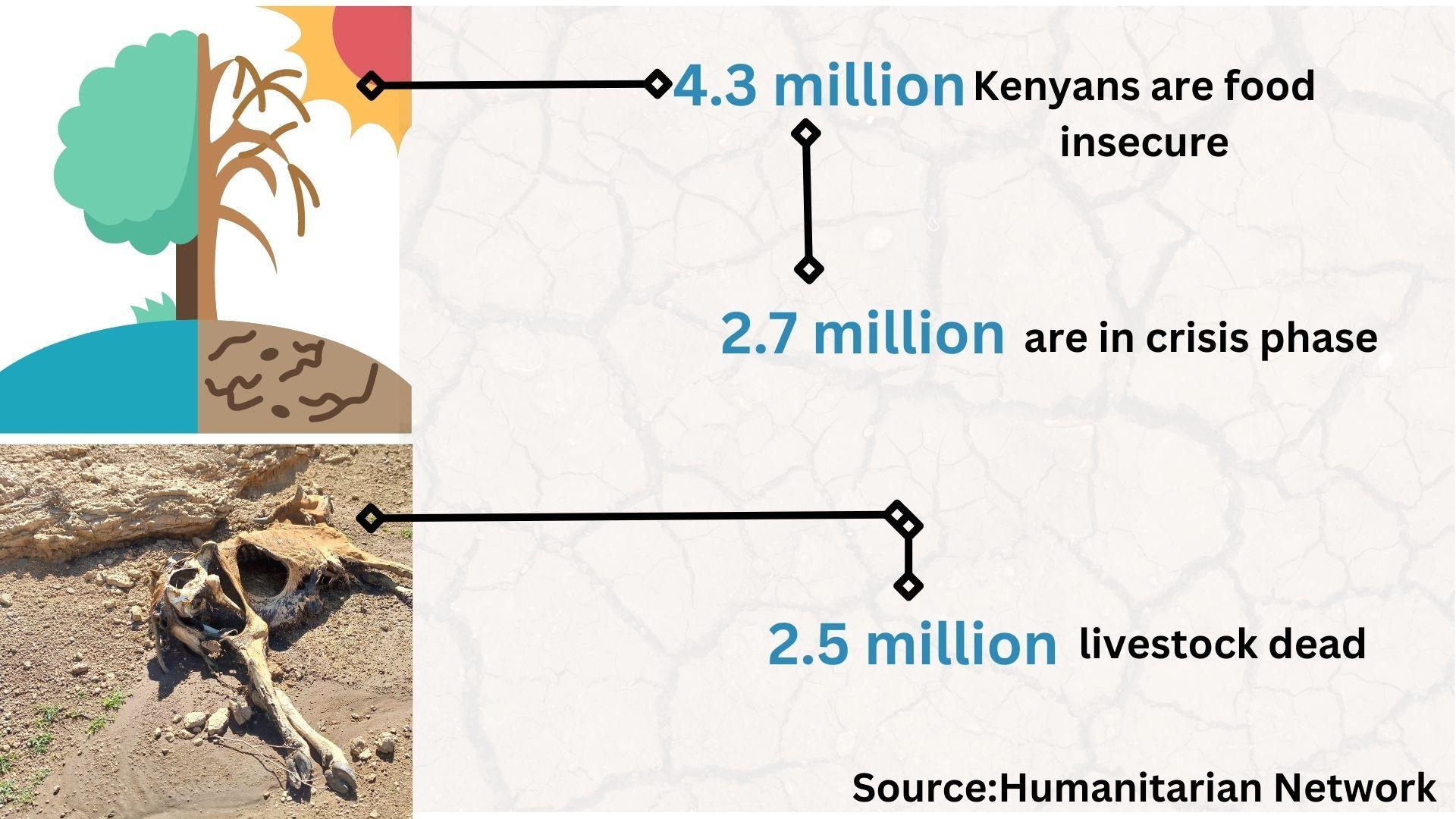

In most villages in the larger Suguta Mar Mar ward in Samburu Central where Lelegwe lives, the aftermath of failed rains is evident; pastoralists possessing a handful of livestock, and men have migrated as far as Isiolo and Laikipia in search of pasture and water for their livestock, leaving women to head households.

The women, abandoned by their husbands, are at the core of family life and the economy of the villages. They have a key role in food production, animal husbandry and raising children.

With nearest water sources running dry, food production has slowed and livelihoods have worsened. What now worries the community most is the ripple effect on their nutritional status.

“Dry seasons are now progressively getting worse. This time, our livestock have perished and left us with nothing,” Lelegwe narrates while weeding her plot. Her family lost 17 cattle and over 100 goats to the drought.

Unfortunately, in Lching’ei, it’s not only the changing weather patterns or conflict with wild animals that the locals are wary of. Armed bandits too have been a cause of pain, injuries and loss of livelihoods as they forcefully break into cattle sheds and drive away with droves of livestock. Every few miles of our journey to meet the farmer was met with pockets of the National Police Reservists patrolling the area to provide security.

Although the government has continued to upscale the security operation against banditry, pastoralist communities are still losing the remaining livestock to bandits. Lching’ei village borders Amaiya and Nasur villages.

However, Lching’ei residents have since found ways of adapting. Every evening, together with their children and livestock, they flock to the Logorate shopping centre one by one ready to spend the night.

“We neither sleep in our houses nor do our animals in the compound. We only come during the day to cook and tend to the crops,” says Mrs Lelegwe, adding that the police provide security at the Logorate centre.

“We are safer at the shopping centre.”

Pirauni Lebarleiya is an agro-pastoralists who used to help his wife water their vegetable garden planted on gunny bags before drought set in and pushed him and the cattle to as far as Isiolo County in search of pasture and water.

“I used to go for water in the dam with my motorcycle to water our vegetables. When drought set in, I took all my sheep and goats to Kilimon area. And later moved with 25 cattle to Ngarantare (Nanyuki-Isiolo border) and later proceeded to Sieku in Isiolo in search of water and pasture. I only came back with three cows,” says Lebarleiya, gazing at his empty Kraal. He lost the rest of the cows to the drought. Lebarleiya reckons that his farming activities have reduced following prolonged drought. Currently, he is preparing a comeback with new vegetable seedlings to transplant in new gunny bags. He used to grow cabbage, sukuma wiki, managu, onions, among others.

Classified as an Arid and Semi-Arid area, Samburu is a water scarce county, and the situation has been getting worse due to the frequent and prolonged bouts of intense drought.

According to the March 2023 Drought Early Warning Bulletin produced by the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA), Samburu County was in the alarm drought phase.

The report further indicates that the majority of villagers accessed water from boreholes and wells. Boreholes and wells were relied on by 40 and 30 per cent of the households, respectively.

Mrs Lelegwe is part of a 30-member Sipat Women Group (formerly Beans Growers Women Group) who have sought out new farming methods to respond and adapt to the changing weather patterns and save their village.

She is practising climate-smart agriculture to diversify her source of livelihood, from solely depending on livestock keeping to other income generating activities like agro-pastoralism.

Until the women group received training on kitchen garden, multi-cropping, seedbed establishment among many other climate smart farming techniques, Mrs Lelegwe and other members of the group engaged in businesses and traditional small-scale farming.

But income from their farming was low and produce did not yield enough profits to sustain the activity.

In 2022, Caritas Maralal engaged an agronomist to train the women group on climate-smart agriculture under the WWF-Kenya’s Voices for Just Climate Action (VCA) funding programme to strengthen indigenous communities’ response and adaptation to climate change.

The VCA project aims to raise the voices and capacity of underrepresented or marginalised groups to enable them take on a central role as creators, facilitators and advocates of innovative and inclusive climate solutions. The mission is to create awareness of how climate change affects vulnerable/marginalised groups such as pastoralists, women, children and people with disability and efforts to alleviate these effects.

“I partitioned the farm as per the lessons from our training and I must admit, the harvest has been plenty and lasted longer than the previous harvests. I’m able to sell to my neighbours and other business people in Longeiwan and Suguta markets and restaurants in Maralal town,” says Mrs Lelegwe.

The aim of the livelihoods diversification programme across the pastoralists region was to rehabilitate farmland in an environmentally sustainable way, and ensure households have a supply of fresh vegetables for food security and nutrition, says Coleta Nyaenya, the programmes manager at Caritas Maralal.

“Women farmers who planted indigenous vegetables recorded improved intake and growth from their children as compared to when they only fed them on porridge (locally known as Kitegen),” Nyaenya says.

“Now the women have become entirely independent. They are now able to sustain their households during drought periods even when their husbands migrate in search of water and pasture for the livestock.”

But in Samburu, as is the case in many parts of ASAL regions, women and children are disproportionately affected by the drought, which has increased their vulnerability to food security, ill health, violence and drastically reduced their access to nutritious food.

According to the ‘2022 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World’ report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s Agrifood Economics Division, the number of people affected by hunger globally rose to as many as 828 million in 2021.

In Kenya, more than 37 million people representing over 80 per cent of the population cannot afford a healthy diet, which has particularly negative nutritional consequences for women and children.

According to a recently released report by Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), at least 970,000 children below five years and 142,000 pregnant women and lactating mothers are suffering from acute malnutrition.

Nationally, one out of five children below five years are stunted, meaning they are short for their age, with a majority living in rural areas, according to the 2022 Kenya Demographic Health Survey (KDHS).

Kepha Nyanumba, consultant nutritionist at Crystal Health Consultants Limited, says kitchen garden farming promotes food and nutrition security.

“It ensures people have access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences,” says Nyanumba.

“It plays a key role in fighting the nutritional deficiencies associated with food scarcity.”

This oasis on the border with Amaiya village has had a fair share of challenges in the quest to grow and consume indigenous vegetables. Until Mrs Lelegwe started irrigating her plot of land using pipes, she used to fetch water from Logorate dam, 500 metres away, to water her crops.

“I started farming in 2019 on half an acre. I planted green pepper, onions, sukuma wiki and tomatoes,” she says.

She would later expand to one acre. “I later bought pipes for irrigation through the help of World Vision. I also bought a generator at Sh35,000 after selling maize from my farm that I used to drain water from the dam and irrigate the field.”

Several kilometers away in Lorrok village, Porro ward, Miriam Lekarabi, 32, has tasted the fruits of climate-smart agriculture.

She says, “Last year I planted sukuma-wiki which I sold at Porro market at Ksh50 (US$0.37) a bunch. I also harvested two full sacks of potatoes, which I sold at Ksh3,500-4,500 ($26-33),” says Lekarabi who belongs to Mayian Village Savings and Loans Group.

Lekarabi and Lelegwe’s practice of climate-smart farming has led to improved living conditions and they are now beginning to put back power in women’s hands and halt the climate migration.

“We now have money in the family, even when the livestock dies due to drought, we live better. Our children too are able to go to school and are feeding on nutritious food,” says Mrs Lelegwe, who has since become a model farmer in her village.

“We now have financial independence and a choice. If we all change our ways as a community and get bumper harvests from our farms, we will get rid of climate-change-induced hunger and malnutrition.”

This story was produced with support from WWF-K VCA project and MESHA