Igembe Central sub-county is one of the driest areas of Meru County and residents rely on rain for subsistence farming. But about 40km from the Meru-Maua road, we find a fenced-off oasis.

The Gakunku wetland is the source of the Bwathonaro river, which snakes through the Igembe region and Meru National Park, giving life to thousands of residents and wild animals before draining into the river Tana.

But five years ago this oasis with lush vegetation and a stark contrast to surrounding areas was threatened with extinction by human activity, with residents invading it and cultivating crops, especially arrow roots.

Alarmed that this would lead to the drying up of the river and threaten the lives of residents and animals, members of the Bwathonaro Water Resource Users Association (WRUA) fenced it off and planted thousands of trees.

“The situation was dire because during dry seasons, like now, there would be a scramble for the little water that came out of the well. Domestic animals would be brought here, residents fetched water from the well while others grew crops. It was chaotic,” said WRUA secretary Riungu Mutea.

With funding of Sh3 million from the Upper Tana Catchment Natural Resources Management Project, the community fenced off the 25-acre wetland, put it under lock and key and formed a committee that placed the area under 24-hour surveillance.

They also incorporated the revered Njuri Ncheke council of elders to help conserving wetlands.

“Since their word is final, we brought Njuri Ncheke elders on board so that they could assist us. They camped in the small forest and threatened residents with a curse should they encroach on the area or cut down trees there. It became a sacred ground and that is how we succeeded in protecting it,” Mr Mutea said.

Residents have also built an intake for five projects, with water serving over 400 households or 3,000 residents. They also ration water during dry seasons by releasing it to the park at intervals.

“Residents use water during the day, while at night we direct it to the park. This has reduced human-wildlife conflicts because animals don’t cross over to our farms,” said committee chairman Wilson Nduati.

The wetland is a relief from the ravaging effects of drought in the area that has seen crops dry up due to lack of rains. Several residents benefit from the water pumped from the well to their farms, where they irrigate their crops, including miraa trees.

Mr Simon Mumbere, the knowledge management and learning officer at the Upper Tana catchment project, said they focus on conservation and management of natural resources in Meru, Tharaka Nithi, Embu, Kirinyaga, Nyeri and Murang’a counties.

“We work with members of the community in the six counties and address practices including over-abstraction of water and pollution, which cause degradation of catchment areas, leading to adverse effects such as human-wildlife conflicts,” Mr Mumbere said.

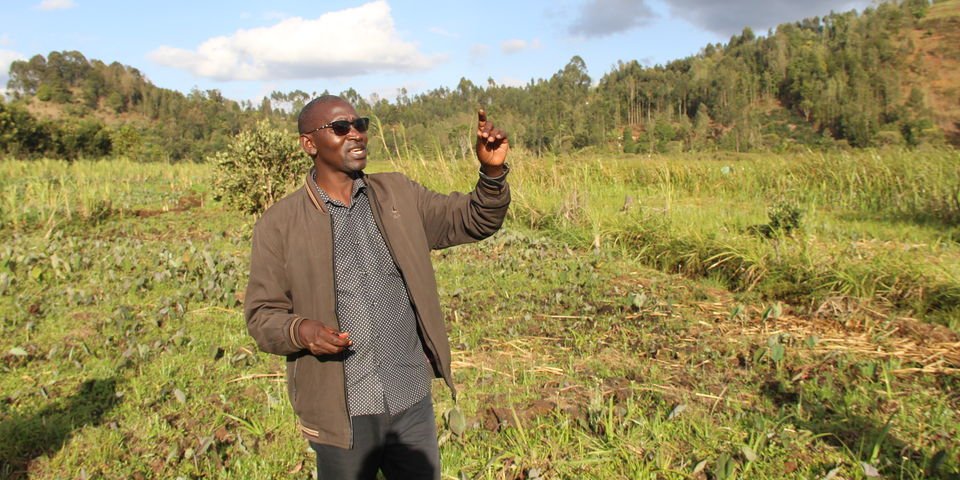

But the Gakunku success story is not reflected in the entire region. In the Maili Tatu area, on the outskirts of Maua, is the Mporoko swamp, a 140-acre wetland that has been invaded by farmers.

Mr Shadrack Kithure, the coordinator of a community-based environmental organization, said they have partnered with other groups to sensitise members of the community on the importance of conserving the wetland.

“We planted 20,000 trees and incorporated elders, who are helping us to conserve the area. Once we plant the trees we hand them over to elders, who instill fear in residents by warning them against cutting down the trees, and it has worked,” Mr Kithure said.

He called on the county government to intervene by fencing off to protect it.

“People have also planted eucalyptus trees in parts of this wetland and this is posing a danger to the catchment area. The government should move in and criminalise this activity or there is the risk that this wetland will dry up,” he said.